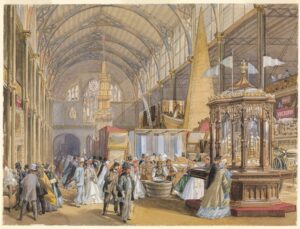

[photo: Nash Australian Section…, London 1862 1863 {1881} SLV [WT]]

Such developments might seem barely relevant to the current project, given Australia’s colonial status, and distance from Europe. But Australia was actually more closely connected with these developments than might be imagined, for instance through the major international exhibitions of the period, both overseas and in Australia (the image shown here, from the present catalogue, shows the Australian section of the 1862 London exhibition in the Crystal Palace).

Admittedly, works by major French realist and Impressionist artists did not enter the collection until after 1904 (beginning with significant recent works by Camille Pissarro and Auguste Rodin, in the first group of Felton Bequest purchases selected by Hall in Europe in 1905). However, a notable precursor was Nozal The Seine at St Pierre {1891} NGV [PA], bought in 1891 on the advice of local painter John Longstaff, while in Europe after winning the inaugural NGV Travelling Scholarship in 1887. This large, atmospheric canvas by Nozal (1852-1929), a painter described recently as working “on the fringes on Impressionism,” provided NGV visitors in the 1890s with a taste of the alternatives French painters had been exploring in the preceding decade or so, markedly more light and colourful than much British and German landscape painting of the same era.

This acquisition dates from what Elena Taylor, in a fascinating recent exhibition and catalogue (2013), describes as a “fleeting moment of Impressionism” in the work of Longstaff (1861-1941), who flirted briefly with the style when painting with John Peter Russell (1858-1930) in Normandy in 1889, before retreating to more academic and eventually highly conservative position in his subsequent career.

Tom Roberts (1856-1931), during his earlier studies in England (1881-84), seems never to have ventured so close to the Impressionists, despite his friendship (and later correspondence with) Russell, who subsequently lived and worked in France, and knew van Gogh, Rodin, and Monet, painting with the latter at Belle-Île in the 1890s.

Just how “Impressionist” the work of Roberts, Conder and Streeton was during the later 1880s and 1890s remains a matter for debate. They did call their famous August 1889 show “The 9 x 5 Impression Exhibition,” and veteran Melbourne critic James Smith, lambasting their work in The Argus, also accepted the label, quoting British distaste for the French “craze,” although, as has been pointed out since, Roberts and his colleagues seem to have been inspired most directly by Whistler.

It has often been observed that the NGV’s failure to buy any of the 9 x 5 works at the time (although several have been acquired since) reveals the institution’s conservativism. But it could hardly have been otherwise, especially with James Smith occupying the role of Chairman of the National Gallery Committee, a position he continued to hold until his death, at the age of almost 90, in 1910. It would seem to Bernard Hall’s credit that, despite Smith’s influential views, paintings by McCubbin, Davies, Streeton and others were purchased for the collection in the mid 1890s – although Roberts was not included, whether because of Smith’s attitude or Hall’s, or both, seems unclear.

Of course, there were also various other significant currents to modernism during the later 19th century, and some of these also figured in pre-Felton acquisitions, for instance the etchings by Whistler and Klinger acquired in 1891-92 (refer detailed entries for further details).

Nevertheless, it would be several decades more before the full implications of modernism were taken on board in Australian culture generally, and at the NGV in particular.

Refs.

For a well-illustrated recent survey of the 9 x 5 Exhibition, see McDonald Art of Australia, 2008, pp.469ff. Whether consciously or not, Smith’s 1889 critique echoed both Ruskin’s infamous 1877 attack on Whistler, and Louis Leroy’s 1874 review of Monet, the source of the term “Impressionism” (used ironically by Leroy): see https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=Exhibition_of_the_Impressionists&oldid=4434659])

See also Taylor Australian Impressionists in France (2013), esp.pp.37ff. (for Longstaff)